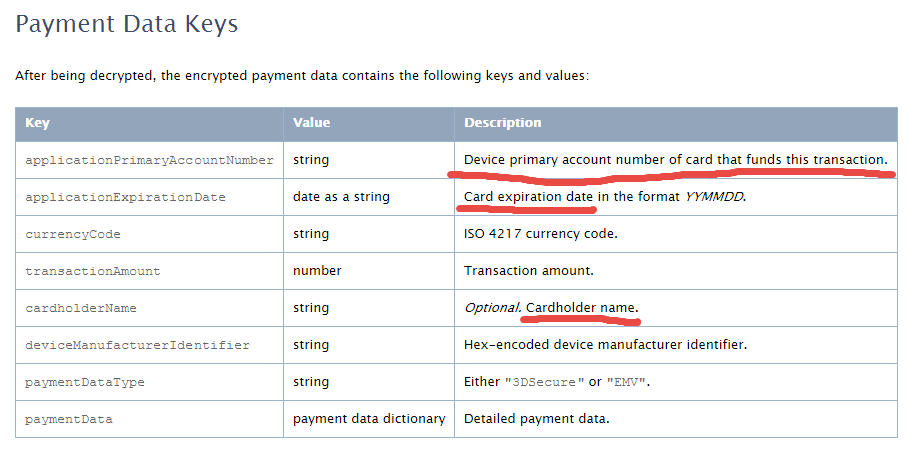

Apple Pay is looking pretty attractive so far from a security perspective. But it’s tokens could be cause for concern...

|

My first take on Apple Pay security in this article published by VentureBeat. Apple Pay is looking pretty attractive so far from a security perspective. But it’s tokens could be cause for concern...

0 Comments

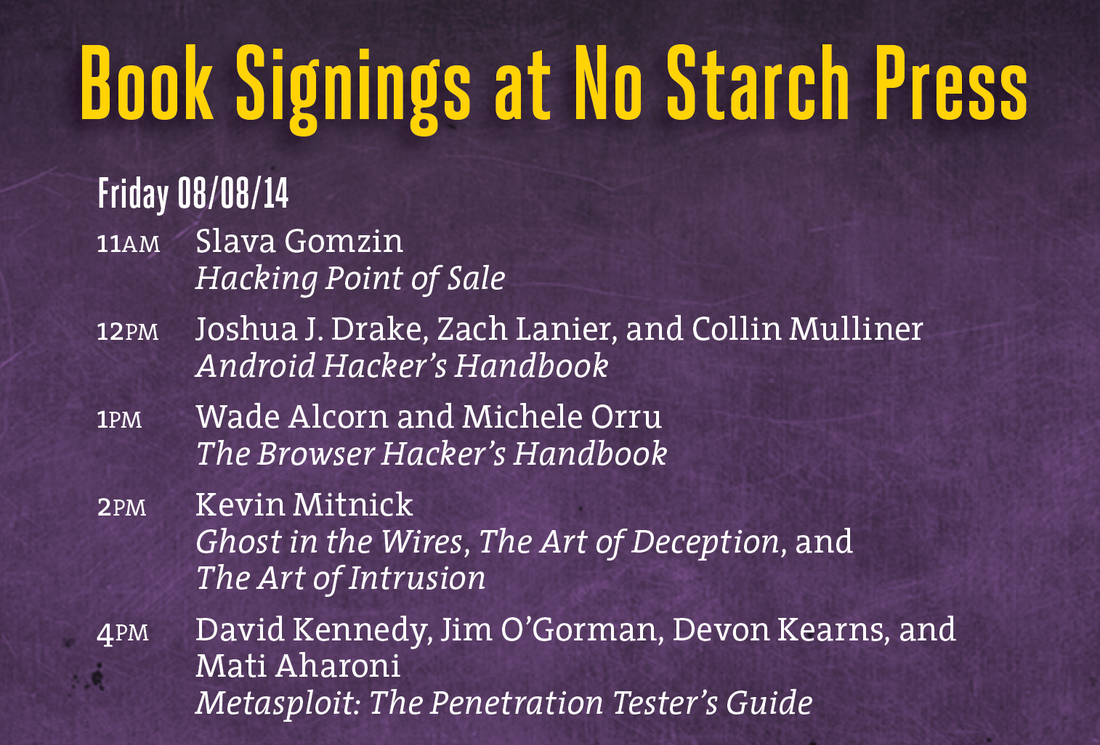

I'll be doing two one-hour book signings at Black Hat USA 2014 and DEF CON 22 conferences in Las Vegas: Black Hat USA 2014: August 6, 2014, 5:30 pm Mandalay Bay Conference Center, Tripwire booth 141 (I'll be doing a short presentation before the book signing) DEF CON 22: August 8, 2014, 11:00 am Rio Hotel & Casino, No Starch Press community table in Vendor Area I don't think the palm scanner as an authentication method will make it into a mainstream of retail payments, at least not in the US. It is bulky, and most important thing - requires significant physical interaction with the device, which customers try to avoid. I believe the future belongs to personal, contactless payment devices and gadgets, such as smartphones and smart cards equipped with biometric sensors, which would allow the buyers to interact with the merchant's payment system without physical contact. Biometric scanner on mobile phone is interesting feature that might be helpful to enhance security of mobile payments, as well as simplify the payment process and reduce the transaction processing time.

There is a new password protection technology available from RSA. They split the passwords in two and store them on two separate servers in two different locations so if one server/location is compromised it does not compromise the whole password. This is interesting idea, but what about performance, and what if both servers are compromised (probably, they are going to be managed by the same entity)?

Interesting analysis of most frequently used passwords - thanks to recent Yahoo security breach:

"• 2,295: The number of times a sequential list of numbers was used, with "123456" by far being the most popular password. There were several other instances where the numbers were reversed, or a few letters were added in a token effort to mix things up. • 160: The number of times "111111" is used as a password, which is only marginally better than a sequential list of numbers. The similarly creative "000000" is used 71 times. • 780: The number of times "password" was used as the password. Apparently, absolutely no thought went into security in these instances." The question is - why were they allowed to set up such a password by the Yahoo software in the first place? BTW - have you changed your Yahoo password after the breach? This article references a research paper describing the attack on different types of cryptographic devices including secure tokens such as RSA SecurID. There is one important detail though: the token (or other secure device) must be physically connected to the computer system in order to allow the attack (like RSA SecurID 800 which has USB connector).

I am significantly less worried about the tokens because it looks like most (important) 2 factor authentication keys are just regular devices without physical connectivity such as RSA SecurID 700. After all, the second factor in 2 factor authentication with tokens means "something you have", so if you lose your device (or leave it connected for long time without reason) you already compromise your security anyway. What I am really worried about is the statement about possible attacks on HSM devices which are permanently connected to server side systems and can be compromised using malware such as a worm or trojan with the payload crafted to crack the HSM keys and compromise the host software: "Hardware Security Modules are widely used in banking and similar sectors where a large amount of cryptographic processing has to be done securely at high speed (verifying PIN numbers, signing transactions, etc.). A typical HSM retails for around 20 000 Euros hence is unfortunately too expensive for our laboratory budget. HSMs process RSA operations at considerable speed: over 1000 decryptions per second for 1024 bit keys. Even in the case of the FFF oracle, which requires 12 000 000 queries, this would result in a median attack time of 12 000 seconds, or just over three hours. We hope to be able to give details of HSM testing soon." Here is what LinkedIn is doing in order to "protect our members": "transition from a password database system that hashed passwords ... to a system that both hashed and salted the passwords". Well, this is great security innovation. They don't even talk about two factor authentication. Many online companies, who take security seriously, already implemented two factor authentication a long time ago . Social networks are not exception: both Facebook and Google have two factor authentication mechanisms.

Two factor authentication and online companies (Google, Facebook and others): http://bit.ly/KMohVO Original post about LinkedIn stolen passwords: http://bit.ly/LzGWzu LinkedIn blog about implementing salted passwords: http://bit.ly/L0iPNd Since I have an active LinkedIn account, recent LinkedIn security breach became a personal issue for me and I decided to investigate it by myself in order to find out whether my account could be compromised. I have downloaded the file, which is -- according to the article published on Russian security news site -- claimed to be a file with stolen LinkedIn passwords, and tried to search for my LinkedIn password (of course, the old one - I changed it as soon as the first information about the breach was posted yesterday), but I could not find it. Here is the explanation of what I have done. First of all, the structure of the password file is weird: it contains 160 bits (20 bytes = 40 ASCII HEX chars) entries separated by dots (0A), but some entries apparently contain 5 leading zeros (i.e. they contain only 140 bits of information). Since there is no such hash function that would produce 140 bits, I tried to hash using SHA1 (which produces 160 bits) and just remove the 5 leading chars from the resulting ASCII HEX string. As I said, my password still did not go through, so I tried to hash some mostly used password dictionary entries -- such as "password" and "abcd1234" -- and I did find (using WinHex - the file size is 245MB) the matching entries for both of them in the file, which means that the file apparently does contain more than 6 million hashed passwords (some of them are left padded with 5 zeros though). However, my findings still do not prove the fact that these passwords are related to LinkedIn. They even do not demonstrate that this file contains any real passwords: it can be a rainbow table. But I still recommend you to change your LinkedIn account password. Just in case. Here is an example of hashed password from the "LinkedIn password file": password: [password] SHA1: [5baa61e4c9b93f3f0682250b6cf8331b7ee68fd8] "LinkedIn password file" entry: [1e4c9b93f3f0682250b6cf8331b7ee68fd8] |

Books

Crypto Basics Crypto Basics

Bitcoin for Nonmathematicians: Exploring the Foundations of Crypto Payments Bitcoin for Nonmathematicians: Exploring the Foundations of Crypto Payments

Hacking Point of Sale: Payment Application Secrets, Threats, and Solutions Hacking Point of Sale: Payment Application Secrets, Threats, and Solutions

Recent Posts

Categories

All

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed