|

Companies and governments are still punch-drunk on data, and have believed the wildest of promises on how valuable that data is. The research showing that more data isn't necessarily better. Many organizations are still downplaying the risks. Some simply don't realize just how damaging a data breach would be. Some believe they can completely protect themselves against a data breach, or at least that their legal and public relations teams can minimize the damage if they fail. And while there's certainly a lot that companies can do technically to better secure the data they hold about all of us, there's no better security than deleting the data. Some organizations understand both the first two reasons and are saving the data anyway. The culture of venture-capital-funded start-up companies is one of extreme risk taking. These are companies that are always running out of money, that always know their impending death date. They are so far from profitability that their only hope for surviving is to get even more money, which means they need to demonstrate rapid growth or increasing value. This motivates those companies to take risks that larger, more established, companies would never take. They might take extreme chances with our data, even flout regulations, because they literally have nothing to lose. And often, the most profitable business models are the most risky and dangerous ones. |

|

0 Comments

Pay attention to this phrase: "The breach took place in June last year but was only recently discovered."

A US health insurer has admitted it has been hacked and the data of 1.1 million of its customers exposed.

I think this article is good starting point for new big discussion: is healthcare going to be the next primary hacking target as the focus is being moved out of PCI which is slowly but surely transitioning towards more secure technologies such as EMV, P2PE, and Apple Pay? Anyway, I like this break down of the problem:

Healthcare companies keep patients’ personal and financial data.Many patients use online payment options, which means their records may have information such as bank accounts and debit/credit card numbers.

It did not take too long before another card data breach occurred, this time at Kmart.

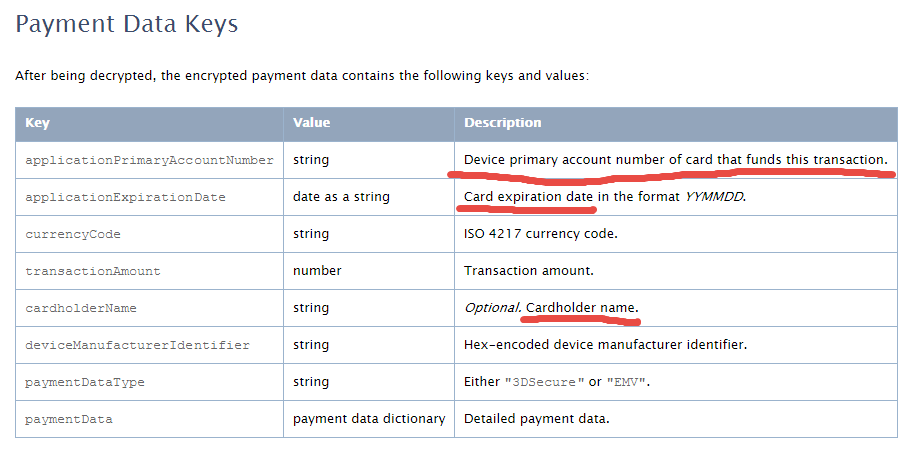

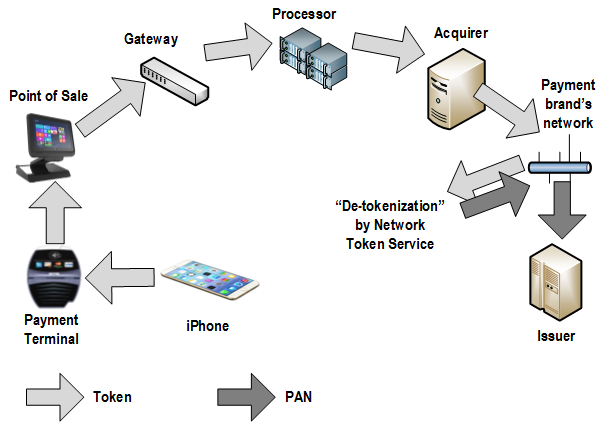

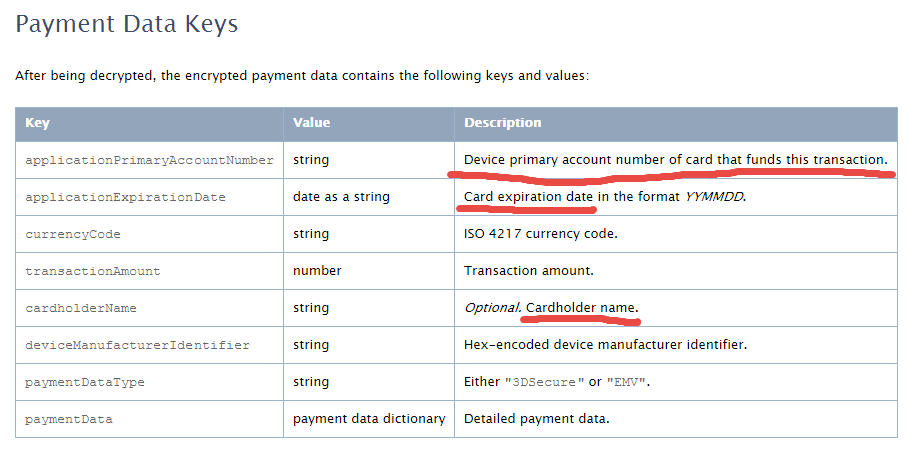

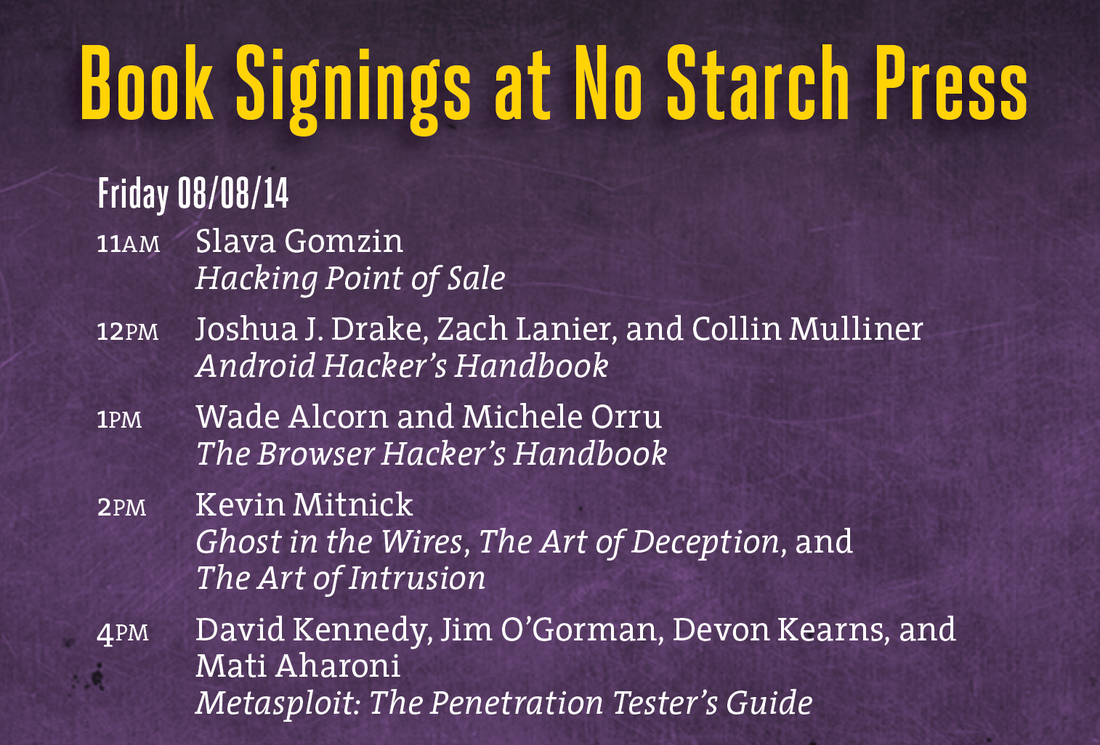

The security experts report that beginning in early September, the payment data systems at Kmart stores were purposely infected with a new form of malware (similar to a computer virus). This resulted in debit and credit card numbers being compromised.  This essay was previously published in VentureBeat on September 25, 2014. Updated with more details about tokenization implementation on October 3, 2014. Apple Pay could be a big deal for the payment industry because — besides all the other business and marketing considerations — it looks pretty attractive from a security point of view. Here’s why: 1. Two-factor authentication on every transaction — “something you have” (iPhone) + “something you are” (fingerprint). The security level is higher than Chip & Signature — “something you have” (your card) — and is similar to chip and PIN — your card as “something you have” plus PIN as “something you know”. However, the biometric fingerprint is usually stronger than 4-digit PIN, which can be guessed or stolen through skimming. Therefore, the Apple Pay’s cardholder authentication is stronger than even chip and PIN, meaning that there are fewer fraud risks for merchants, issuers, card brands, and service providers. 2. Using tokenization technology, however it is implemented or called, means that merchants are not exposed to card data in clear text, which in turn means that the merchant’s payment acceptance systems do not have to be PCI compliant anymore. Unfortunately, this does not help traditional retailers much, since their systems (POS + payment terminal) must be PCI compliant anyway in order to process regular payment cards. However, it opens the door for a new way of payment acceptance — virtually, any device with NFC chip (for example, a business or even consumer grade laptop or tablet) can “legally” accept Apple Pay and not worry about PCI compliance. Of course, this statement requires some proof, that’s why I am looking for more details about Apple Pay’s tokenization system. The security of Apple Pay’s tokenization system is still questionable. Based on information I found so far, the payment token (at least the one used for in-app purchases, as the company has not released enough technical details about in-store purchases) contains encrypted cardholder data — primary account number, expiration date, and cardholder name — which in my opinion reduces the Apple Pay security score a bit. Below is the fragment of Payment Token Format Reference from the PassKit reference. It is still unclear whether this is the token format that is being sent from the iPhone device to the payment terminal during an “in-store” Apply Pay session. However, according to Apple, “The PassKit framework provides APIs for Apple Pay. The StoreKit framework provides APIs for In-App Purchase.” There is another statement from the same Getting Started with Apple Pay document that proves that the payment tokens (and therefore iPhone’s secure element) contain encrypted card data: “The alternative is to provide your own server-side solution to receive payments from your app, decrypt payment tokens and interface with the payment provider.” Note that this statement specifically targets the in-app purchases, and I am not sure whether the same token is used for in-store purchases or whether the in-store token, even if it has the same format, in fact contains the card data. In any case, it looks like at least the in-app purchase token does contain the encrypted cardholder information. This fact contradicts Apple’s claim that no card data would be stored on the iPhone device. Usually, “no card data” means that there is no cardholder data at all, even in encrypted form. Some tokenization implementations, for example, use randomly generated tokens that cannot be reversed back to the original PAN (primary account number). How difficult is to trick the Apple Pay system in order to decrypt the payment token and retrieve the original card data? That’s still an open question, but I am sure hackers have started thinking about it already. Another question is whether Apple is using the same token (or the same data inside the token) for in-store purchases, i.e. whether the in-store token contains the same card data elements as the in-app token. I hope Apple will release more technical details about its “in-store” tokenization technology to the public so security experts can review it, calculate the risks, and determine the level of security. Update on tokenization implementation, October 3: Apparently, Apple Pay uses "network tokenization" - a technology implemented by payment brands (Visa, MasterCard, Amex) and supposedly based on common "EMV tokenization" approach (the spec was released by EMVCo in March 2014). There is a confirmation at least from Visa for the first part. However, unfortunately, there is no official confirmation for this information from Apple as well as there are no technical details available about Visa Token Service or other brands' tokenization implementations (for example, whether they are compliant with EMVCo spec or not) . Anyway, such implementation scheme, with connection between "network tokenization" (like Visa Token Service) and "EMVCo tokenization", would make sense. Let's assume this is true so we could imagine how it works before we get the actual details. "Network tokenization" would address some concerns expressed in my original article and provide answers to some questions. For example, it explains the "device primary account number" field in the picture above. In the "network tokenization" scheme, the token looks the same as the original PAN (19 digits starting from the payment brand's identification prefix such as "4" for Visa) . "Device PAN" probably means that the token is encoded in this field rather than the original PAN. "EMV tokenization" uses the format-preserving token which looks like regular PAN but has a special BIN range dedicated by the payment brands for tokens. Thus, the fact that the token is used instead of the original PAN is transparent for existing merchant and payment processing systems. "De-tokenization" is done by payment network (Visa, MC, Amex, etc.) - after transaction authorization request passes the gateway, processor, and acquirer, but before it hits the issuer. This is the first main difference of EMV tokenization from "classic" tokenization implemented by payment gateways and processors, where transaction is "de-tokenized" before it even reaches the acquirer and the network. Second difference is the way the token is generated and consumed. In "classic" tokenization, the token is usually generated at the back end (merchant's, gateway's, processor's, or acquirer's data center) - only after the authorization request is processed using cardholder data in clear text. This is necessary in order to deliver the original PAN to the point of tokenization which is located at the data center far away from the merchant's point of sale. So the cardholder data is still vulnerable for attacks, unless it is protected by point-to-point encryption, which is still relatively rare due to its high implementation costs for merchants. In Apple Pay, the token is generated and stored in iPhone (the exact details of this mechanism are still unclear so it is a whole separate topic for future research and post). Therefore, the cardholder data in clear text never travels through the merchants' systems. And third difference: since Apple Pay apparently uses EMV Contactless protocol for communicating the data between the iPhone device and merchant's payment terminal during transaction, the token is always accompanied by the cryptogram - a piece of additional dynamic encrypted data which changes for each transaction and allows the payment terminal and the tokenization system to authenticate the cardholder and validate the token. Hopefully, the token is invalid without the cryptogram, otherwise, it could potentially be used just as regular PAN for any transaction. Finally, some good news for consumers and merchants: there is an indication that "Apple Pay like" systems can be implemented by other mobile payment providers. Here is important quote from Visa website which is worth mentioning: Now you can offer consumers a broad range of simple digital payment options, while protecting their sensitive information from fraud. Whether you want to enable mobile payments with Apple Pay or Android devices, create a frictionless e-commerce experience with Visa Checkout, or securely maintain cards on file, Visa Token Service provides the unifying platform. It means that the payment brands do not intend to keep their tokenization technology limited for Apple private use only, and so payment solutions similar to Apple Pay can be implemented by other mobile payment solution providers such as Google. Although all these assumptions sound reasonable, many of them still require official confirmation and additional explanation which are highly anticipated from Apple. My first take on Apple Pay security in this article published by VentureBeat. Apple Pay is looking pretty attractive so far from a security perspective. But it’s tokens could be cause for concern... It becomes more and more difficult to comment on card data breaches. The news about another attack on US merchant – similar to recent Home Depot card data breach -- are coming almost every day. The scenarios of attacks -- as well as the tools used to penetrate the merchant network and retrieve the sensitive cardholder data -- are always the same or very similar. The security solutions -- which could potentially prevent those breaches but have never been tried -- also remain the same. And nothing changes, so there is no much to talk about... When you swipe your card in retail store anywhere in the US, the possibility to lose your money today is higher than when you gamble in Las Vegas. Unlike casino, however, in many cases, eventually you can get your money back (I can't tell the same about the merchant though). It's like a total loss insurance play: you recover your money (at least, partially) but never get your beloved car back. And so there are things -- including consumers' trust and confidence in card payment system -- that will never return to the original state. So what's next - are we going to move back to cash? I doubt it. Plastic cards are too convenient to be abandoned. For many people paying with credit card became a habit so strong that it would require a treatment similar to the one necessary to quit smoking. I don't use credit cards (whenever it’s possible) because I think the idea of paying with credit for day-to-day things is totally wrong. But I still use debit card everywhere. And it is much more convenient than constantly taking care of carrying significant amount of cash which is necessary for daily life activities. So it looks like finding solution for payment card security problem is inevitable. EMV (chip cards) and Bitcoin (crypto currency) technologies partially solve this problem for brick-and-mortar and online transactions respectively. Since EMV cards are still vulnerable when used for online purchases (and sometimes in physical store as well!), and Bitcoin currently is not suitable to be used in brick-and-mortar merchants, there is no ultimate solution. Perhaps, we should wait until next emerging technology that would combine all the good features of EMV and Bitcoin while being as convenient as plastic cards. Recent card data breaches at Supervalu and Albertsons retail chains are just the latest in a long series of high-scale security incidents hitting large retailers such as Target, Neiman-Marcus, Michael’s, Sally Beauty, and P.F. Chang’s. These breaches are raising a lot of questions, one of the most important of which is: Are we going to see more of these? The short answer is yes; in the foreseeable future we will continue to see more breaches. Here’s why: 1. PCI DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard) is failing to protect merchants from security breaches. The original idea behind PCI DSS, which was created 10 years ago, was that the more merchants we have that are PCI compliant, the fewer breaches we’ll see. The statistics shows the exact opposite trend: Most merchants who recently experienced card data breaches are PCI DSS compliant. The problem is that, in the 10 years since PCI DSS debuted, the standard hasn’t evolved to address the real threats, while hackers, who have already learned all the point-of-sale vulnerabilities, have been constantly working to enhance their malware. 2. Merchants and service providers are still not widely implementing P2PE (Point-to-point Encryption) technology, which is the only realistic way to address the payment card security problem. Despite the strong support for P2PE from the payment security community, only four solution providers are certified with the PCI P2PE standard, and at least two of them are located in Europe. The problem with P2PE is that it is very complex and expensive and requires very extensive software and hardware changes at all points of transactions processing — from the POS (point-of-sale) in the store to the back-end servers in the data center. 3. Retailers introduce new payment hardware, including tablets and smartphones, that are neither designed nor tested for security issues they face in the hazardous retail store environment. PCI DSS does not address directly any mobile security issues. 4. Updates and new features to POS and payment software open up new risks. Merchants want more features in their software in order to stay competitive. POS software vendors provide those features atop of existing functionality by supplying endless patches. The complexity builds up, extending the areas of exposure, and security risks grow accordingly. Those risks are not necessarily mitigated by continuously updated software. 5. Vulnerable operating systems make it easier for hackers to penetrate a network and install malware. Most POS systems are running on Windows OS, and some retailers are still using Windows XP, which Microsoft has not supported since April 8, 2014. We don’t know how many “zero-day” vulnerabilities are out there, but we know for sure that those vulnerabilities, even if they are discovered and published, will never be fixed. 6. The traces of many card data breaches often lead to Russia. While the main motivation for all of these attacks is probably still financial, the modern Russian anti-Americanism also encourages Russian hackers to attack U.S.-based merchants more as an act of patriotism rather than a crime. This is a new reality that is different from what we had just a few years ago. 7. Finally, EMV technology, which is supposed to “save” the payment card industry, is not a silver bullet solution. Although this is a topic for full separate article, let’s at least just briefly review the EMV problems and see why it’s not going to bring a total relief. ● Even if the U.S. starts to transition to EMV immediately, it may take a few years until the majority of credit cards are chip cards. During this interim period and even beyond that, merchants will continue accepting the regular magnetic stripe cards, so they will be still vulnerable to existing attack vectors. ● EMV does not protect online transactions: You still need to manually key in the account number when shopping online. Online transactions will be still vulnerable even after full EMV adoption, and for many retailers ecommerce is a constantly growing sector. ● Although EMV is more secure than magnetic stripe technology, there are a lot of vulnerabilities in EMV, and many of them are still undiscovered, or their exploits are not yet well developed. Today, when there are so many U.S. merchants accepting magnetic stripe cards, hackers aren’t bothering to research EMV security issues. But once the EMV transition is done in the U.S., the global focus of attacks will shift away from magnetic stripe cards to EMV and ecommerce. I like this excerpt from Dan Geer's keynote at Black Hat USA 2014: Our choices are Freedom, Security, Convenience -- Choose Two The full transcript of the keynote is available here. I'll be doing two one-hour book signings at Black Hat USA 2014 and DEF CON 22 conferences in Las Vegas: Black Hat USA 2014: August 6, 2014, 5:30 pm Mandalay Bay Conference Center, Tripwire booth 141 (I'll be doing a short presentation before the book signing) DEF CON 22: August 8, 2014, 11:00 am Rio Hotel & Casino, No Starch Press community table in Vendor Area |

Books

Crypto Basics Crypto Basics

Bitcoin for Nonmathematicians: Exploring the Foundations of Crypto Payments Bitcoin for Nonmathematicians: Exploring the Foundations of Crypto Payments

Hacking Point of Sale: Payment Application Secrets, Threats, and Solutions Hacking Point of Sale: Payment Application Secrets, Threats, and Solutions

Recent Posts

Categories

All

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed